- Home

- Ron McCallum

Born at the Right Time Page 10

Born at the Right Time Read online

Page 10

By the late 1970s, most students either had, or had access to, a cassette tape recorder. Accordingly, I asked students to read their essays or assignments onto tape and to hand in a cassette tape with the written copy of their paper. Invariably, in each year one or more of the young men would ask if it would be okay for their girlfriends to read their assignment onto tape. They would usually say, ‘She has a better voice than I do.’ Of course I gave them permission, but I made it clear that a feminine voice would not in any way alter my marks.

Dealing with examination papers, which are always handwritten, is hard for me. Even today, I have to find readers who are willing to battle with student examination handwriting to decipher the words and to read them to me. It really takes all of my concentration to listen to exam answers and to mark them fairly and accurately.

Forty years ago, the Japanese approach to labour relations was taking the western world by storm. This was perhaps due to Japan’s then economic ascendancy and also because of its cooperative processes in labour and in business. In February 1981 I travelled to Japan for two weeks with several Monash colleagues. This was a good opportunity to develop my knowledge in the broadening field of comparative labour law.

Before commencing my travels, Lois had attempted to teach me to eat with chopsticks and I had even learned a few Japanese phrases. I had also read a good amount of Japanese history. Mum was not really happy about me going, perhaps because she remembered how our prisoners of war had been treated by the Japanese.

My memories of Tokyo and of Osaka are of wall-to-wall people, the smells of Japanese food and the very efficient subways. Much has changed over the past thirty years, but at that time Japan seemed to me to have a medieval foundation with an industrial and technological upper stratum laid over it. From my limited observations most blind people were still employed in sheltered workshops, and blindness was seen as a type of shame. It was strange to observe such a technologically advanced society that still had notions that disabilities were karma, and that they perhaps resulted from the past sins of ancestors.

When visiting Japan’s second city, Osaka, I was taken into the office of an official by a young secretary who must have been much shorter than me. More importantly, the door’s lintel was lower than my height and, because she forgot to tell me to duck, my forehead crashed into it. I did not understand the Japanese words the official uttered to her, but his tone was stern.

My lecture was on a comparison between Australian and Japanese labour law, and the Japanese commentator was the famous Professor Tadashi Hanami. In our short time together, we got to know one another reasonably well. Tadashi seemed to me to be as much a sociologist as he was a lawyer, and through this lens he patiently explained to me how Japanese cultural and familial practices moulded their labour laws.

I asked if I could visit a pre-school, and so the authorities arranged for me to be taken to one in Tokyo, where I found the children to be highly disciplined. They spoke to me through a translator and thought I was an American.

My colleagues were travelling on to China, but I had decided that one country was enough and that I would fly straight home. When several Japanese officials learned that I would be flying home on my own, they were greatly disturbed. One of my colleagues, who was our negotiator and spoke Japanese, learned that the airline might not be willing to have me as a passenger travelling unaccompanied, and some negotiations were required before it was decided that I could fly home solo. A car came to meet me, and it took me right to Narita Airport, where I was whisked through customs. When I was sitting in my seat with my seatbelt tightly clipped, a Japanese steward came up and said in her mellow voice, ‘Safety instructions in braille.’ She handed me the booklet, but to my dismay I couldn’t read Japanese braille at all. I told her this and she was crestfallen.

Thinking back, I am sorry that I said anything. I could have simply felt the lines of dots and after a while handed it back. I didn’t go to the toilet for the whole flight or even get out of my seat, and was very pleased when we landed safely back in Sydney. However, I had fallen in love with Japan, and I returned in 1983 to give a few more lectures.

8

Performing Superhuman Acts, and Rediscovering Spirituality

I think it is the case that we persons with disabilities often set ourselves superhuman challenges to demonstrate to everyone else that we are normal. The truth is, people either accept us or do not accept us for what and who we are and, no matter how many activities we skilfully perform, these feats rarely change people’s minds.

In 1981 I decided my next, huge challenge would be to live overseas by myself again. I would do this by going on sabbatical leave—in other words, by taking time to do research free from administrative and normal teaching duties. University academics are able to apply for six months’ sabbatical leave every three years.

When I began as a university teacher in the mid-1970s, it was only possible to take periods of sabbatical leave at overseas universities or research institutes. Australia’s ‘cultural cringe’ was again the culprit. It was not an option to take sabbatical leave and remain at one’s own university.

If I was going to take sabbatical leave I would have to live overseas on my own, which meant that, once again, I would have to find an apartment, learn to get to and from the Law School, shop, cook and find enough readers to aid my work in a foreign country. This would be my supreme challenge. I would show everyone that, despite my blindness, I could do it. Looking back, perhaps it was also the case that, as the challenges of marriage and of fatherhood seemed beyond me, I needed a big task to keep myself together.

Professor Bob Baxt had taught me at Monash and had later become the Dean of the Monash Law School; in 1981 he told me that the Dean of Duke University Law School would be willing to take me for six months. Duke University is situated in North Carolina in the United States and it has a deservedly high reputation. In November 1981 I received a letter from the Duke Law School confirming the arrangements. I would teach at Duke during the 1982 fall semester; that is, from the end of August to December 1982.

Mum was not at all happy about my going. Her attitude was very different from when she gave her blessing for me to study in Canada a decade earlier. I think she felt that I had already proved myself and could not see the use in me doing it all again. Of course she had no understanding of what I would need to do to advance in academia. Lois was sort of resigned to my going; she said that she would come to visit me. By this stage my brothers and I were living very different lives: both were married with young children.

I vividly recall flying from Melbourne to North Carolina on Sunday, 1 August 1982. My parting from Mum was a little strained, but I wasn’t for turning back. Off I flew, feeling somewhat empty inside. I landed in Los Angeles and was shown through customs before taking planes through to the East coast. I arrived late at night and took a cab to Durham, where Duke University is situated. I remember the pervasive smell of the tobacco leaves grown at that time in this part of America. Exhausted by the arduous journey, I stayed at a student hostel for the night. I met people from the Law School the following day.

Judy Horowitz, who was the spouse of a professor who taught labour law, helped me settle into my new home. She took me shopping and showed me around my apartment, which was in a complex of apartments for graduate students. The Faculty thought I might be more comfortable there, and how right they were.

There were three storeys of apartments, and mine was on the ground floor. Several of the other apartments were occupied by married theology students. What really made the difference for me during this six-month period was the kindness of these neighbours—they believed in Jesus Christ and in God.

My family was Catholic, but we were really cultural, as distinct from religious, Catholics. As a university student, I had drifted away from going to Church because the sermons to which I had been subjected were not at all inspiring; they lacked depth. Later on, I decided that there didn’t seem much room for single peo

ple like me in parish churches.

But when my American theology neighbours took me to their Church, I learned the significant role of churches as social institutions in the United States. I thought more about God, and gave thanks for the extraordinary world in which we live. I owe these young budding ministers a great deal.

The daily realities of being blind and living independently obviously still existed. Just like when I was in Canada, or for that matter back home in Australia, I dealt with them in the United States.

My apartment neighbours took turns taking me shopping, and even cooked me meals. One of them, Leslie, would often walk with me to Duke, where she had an administrative job. They initially laughed when I put up a clothes line and they told me that the apartment people would take it down; but this never happened. After I left, my colleagues used it and called it the Ron McCallum Clothes Line. There were no washing machines in our apartments, so each week I had to take my clothes to a communal laundry; but I found my clothes smelt nicer after being dried in the sunshine than they did when they were put in those big dryers.

Actually, doing my own washing was a little complex because the laundry was some distance away from my apartment. One Saturday morning I arrived with my washing in a big plastic bag. When I opened the door, a man asked me if I knew how to work the machines. He said that his wife had gone away for a couple of days, and he hadn’t done the laundry before. I showed him the ropes. By my accent he knew that I was foreign and I told him I was an Australian. He then said, ‘Well, why don’t you see some of the countryside? Why not take my car out this afternoon for a drive?’ When I explained that I was blind, I think he almost dropped all of his clean washing.

It was George Bernard Shaw who said that England and America were divided by a common language. I remember being very sleepy when Judy had explained to me how everything worked in my apartment, including the stove, which she called the cooker. She showed me the broiler and I had no idea what she was talking about. A couple of days later, when I phoned either Mum or Lois, I learned that the broiler was the name of what I knew as the griller.

Early in my stay, several of the Faculty took me out for a meal. Of course, what we call the entrée, Americans call the appetiser, and they call our main course the entrée. I was still a little jet-lagged and in this situation, my lack of sight was a real disadvantage. One of my colleagues asked me if I would like an appetiser. I didn’t know what this was, so I said, ‘No, thank you.’ I was then asked whether I wanted an entrée; but, as I thought there would be a main course to come, I again said, ‘No thank you.’ Then came dessert, and I asked what had happened to the main course.

Professor Jack Pratt initially showed me how to walk the mile or so from the apartment complex to the Law School. This required me to navigate some traffic, but Jack had an instinctive knowledge of my mobility needs and capacities. A young man from the North Carolina Blind Association also came and gave me mobility help and even drew a braille map for me.

Duke University is in a beautiful setting with forest areas close by. When walking to and from the Law School, I loved the smells of the greenery. Some years ago, I read the American novel Cold Mountain, which is set in the Carolinas during the American Civil War, and the descriptions of the bird sounds brought back to me the songs of the birds in the forest areas near Duke. Those bird tweets were far softer than are the sounds of our Australian birds.

There were a few hazards on my walk to and from the Duke Law School, and perhaps I should have taken notice of the old adage that accidents occur close to home. There were big poles holding up the verandas of the apartment complex. One Saturday after I had been at the Law School in the morning I walked home for lunch. While relaxing as I got close to home I hit one of the poles very solidly. I got to my door, opened it and I think I collapsed on the floor. When I woke up several hours later, I drank some water and got myself to bed. I’m pleased to report I had no other major accidents during the semester.

In some ways that I don’t fully comprehend, I found my lack of vision to be more of a handicap at Duke than I ever did at Queen’s University. Perhaps it was because the Australian way of living has more in common with Canada than with the United States. For example, I did not immediately comprehend how formal America’s prestigious universities are. In particular, I didn’t appreciate the status of the Duke Law professors. I’ve always been pretty casual, and in my seminar course of half a dozen students, I asked them to call me Ron. They did so, but they were surprised by my unusual attitude.

Lois did visit me at Duke for a couple of days. I took a week off and Lois, her husband, Keith, and I flew to Germany. This was my first trip to Europe. Keith had a conference to attend in West Berlin, so I kept Lois company. One afternoon, Lois took me on a tour into East Berlin. After the noise of the west, it was deathly quiet. If you had told me that the Berlin Wall would come tumbling down in seven years’ time, I would not have believed you. This became a lesson for me that it is nigh impossible to predict our own future, let alone the future course of nations.

Thanks to some funding, I was able to pay several students to read to me. I also received a series of labour law and related books on tape from the American Recordings for the Blind Inc., so I really was able to learn a great deal of American law.

The academic highlight for me at Duke was attending Jack Pratt’s lectures on American legal history, for these gave me a much better idea of how American lawyers think. For example, in American law there are various codes, such as the uniform commercial code. I think that these originated in the optimistic beginnings of that country, when it was thought that all laws could be written down in codes so that everyone would clearly know the rules. In other words, codes would assist people to know right from wrong. The practice in Australia has been quite different, with much greater emphasis placed on statutes and the common law rulings of the courts.

In time I discovered I really enjoyed American pork, which is much sweeter than our Australian variety. I well remember late evenings with George Christie and his wife, Debbie, drinking gorgeous Californian wine. George was an outstanding academic in tort law and in jurisprudence. He was rather conservative, but very gifted.

On 3 January 1983, I flew home to Melbourne. I felt more mature and ready to face the coming years of teaching and of writing. At that stage I decided that I didn’t need any more challenges for the moment, but just to live and to learn.

From when I commenced teaching in 1974, right up to 1985, Australian labour law underwent significant changes. In the late 1970s, for example, state statutes outlawed discrimination at work, and this culminated with the federal Sex Discrimination Act 1984. In 1983 in New South Wales, and in 1985 in Victoria, new occupational health and safety statutes were enacted. These were modelled on recent British laws that placed broad safety duties upon employers, upon contractors and also upon employees.

In 1983, the Hawke Federal Labor government commissioned an inquiry into industrial law, and this marked the beginning of a re-appraisal of our compulsory conciliation and arbitration system, which was starting to come under pressure. By the 1980s, most goods that were either imported into, or exported from, Australia were transported in standard containers, which were loaded and unloaded by gigantic cranes. Long gone were the days when waterside workers manually loaded and unloaded cargoes. The use of containers greatly sped up global trade, and the word ‘globalisation’ entered our collective vocabulary.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, world trade had suffered from two world wars, a major depression and the Cold War. It was not until 1989, when the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, that levels of world trade reached those of 1914. The changes in information technology meant that commercial contracts and the payment of money could be concluded in seconds at the push of a button.

Competition in international trade is fierce, and inevitably this type of competitiveness spread to Australian workplaces. After all, we now had to compete in the world market for goo

ds and services. The Australian dollar had been floated, and the tariff walls that had protected our local industries were being dismantled. It became clear that we could no longer fix wage rates throughout entire industries. Instead, the demands of competition made it necessary to increase flexibility to enable individual enterprises to make their own arrangements over wages and work rules. These new circumstances needed to be synthesised and dealt with in labour law courses.

In 1983, I began to teach postgraduate subjects in labour law in the Monash Master of Laws program. This was both challenging and exciting. In 1983, I taught comparative labour law, and in 1985 I began teaching occupational health and safety law, and I have continued working in this field ever since. My students are still among my greatest joys.

Don Carter had taught me labour law at Queen’s University. Don, Cathie and their two boys spent a year on sabbatical leave at Monash University during which, in the second half of 1984, Don and I jointly taught a course on employment law. We travelled together to Tasmania after Christmas for ten days’ holiday, driving around that beautiful island.

I woke up early on New Year’s morning, and I was very quiet because I was sharing a room with Don’s boys. I wanted to listen to ABC FM because 1985 marked 300 years since the birth of Bach and Handel. I remember lying there listening to Bach on my Walkman earphones, wondering what this new year would bring. Little did I imagine falling in love.

9

Losing My Beloved Mother, and Falling in Love with Mary

From what I have so far written, it will be obvious that my knowledge and experiences with women had been quite limited. Attending special schools, then an all-boys school, having no sisters and my family circumstances all played their part. My decision to become a legal academic when my only technology was tape recorders meant that my work took up much of my time. I had very few moments free for nurturing relationships.

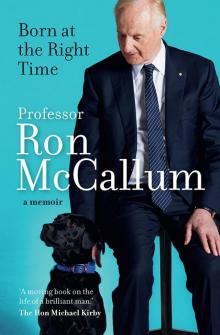

Born at the Right Time

Born at the Right Time