- Home

- Ron McCallum

Born at the Right Time Page 15

Born at the Right Time Read online

Page 15

While I was helping Gerard, Daniel, whom we had not strapped into the stroller, got up and toddled after Mary. When I realised that Daniel had gone, I reached out towards other passengers in the crowded terminal saying, ‘Have you seen my baby?’ No one answered.

Just then, my old mentor Harry Glasbeek arrived to meet us and Mary came back with the luggage. She instantly realised that Daniel was missing; she was as distraught as I was and ran around calling for assistance. To our immense relief a lovely airline hostess who had picked up Daniel put him back into Mary’s arms. She explained that she had found Daniel trying to walk up the down-escalator. I think that Mary and I were both crying with relief.

My second memory is a special one, which at the time I did not fully appreciate. We rented a two-bedroom apartment in a York University building that also housed a day-care centre. Both boys attended the day-care centre, which freed up time for Mary and me to do our work. The classes Mary attended commenced at 9 a.m., so she would take Gerard down to the day-care centre at about 8.30 a.m. and then walk across to the Osgoode Law School. I would look after Daniel until I took him downstairs shortly before 10.30 a.m.

This was to be my only lengthy experience of routinely spending time caring for a twelve-month-old baby. Daniel and I really got to know one another. Even as a baby, he was a rather musical child and was very aware of all the sounds around him. Like many dads, I guess, I look back at those few months partly with nostalgia, and partly wondering why my busy working schedule did not leave me with more time to spend with the children during their early years.

I still chuckle about my third memory. We parents were required to spend a few hours assisting the staff at the day-care centre each month. One morning in late November 1990, I found myself on duty with Gerard’s three-year-old group. I had not worn a coat when I took Gerard downstairs to the centre that day. It was very cold outside and I assumed that nobody in their right mind would let the children play outside. Well, I didn’t really know Canadians. So, there I was, helping young ones into coats and hats, before setting out into the playground myself without a coat. Thankfully we all came indoors about forty minutes later. I went straight upstairs to our apartment and had a small scotch to warm me up before setting out to walk to the Osgoode Law School.

While Mary, the boys and I were living in Canada I purchased my first ordinary computer. With the help of an information-technology advisor in Toronto, I used an early program with an attached speech synthesiser to read out what appeared on the computer screen. Now I could borrow files from colleagues and simply have them read out to me by the computer.

Of course, if you think for a moment, you will appreciate that it is not easy to design a speech synthesiser program. A screen is two-dimensional, whereas speech is linear—that is, it is one-dimensional in form. The computer user with vision can simply glance at the screen and take in what information is important to them. However, a blind user can only listen to the speech-synthesised words. It would be annoying for the blind user if the program and the speech synthesiser simply read continuously through all of the material on the screen from top to bottom. We don’t need to read everything on the screen all at once. However, the blind user does need to know what they are typing and whether any error messages have popped up. This took some working out by inventors and programmers. It was relatively simple to write computer programs for us blind when the ordinary computer software was straightforward. However, when the Windows programs came along, it took inventors and computer programmers some time to write programs that would speak out what came onto the screen when operating the Windows system. The early programs were a little primitive, but soon enough we blind were able to use Windows relatively easily. Other assistive-technology programs helped those of my sisters and brothers who are partially sighted by increasing the size of the text on the screen.

We arrived back in Melbourne in January 1991. Mary and I wished for a third child, and after two boys we really longed for a daughter. In late April 1991, Kathryn, known always as Kate, was conceived.

At about twelve or thirteen weeks’ gestation, Mary left me at the Monash Law School and went to her ultra-sound. She took with her a couple of friends who were experts at reading foetal pictures. Mary then excitedly phoned me to break the news that we were having a daughter. ‘Kate’, which had been our preferred girl’s name since our courting days, had already been written on Kate’s ultra-sound picture, which is still in her baby photograph album.

In mid-July 1991, an advertisement appeared in The Australian newspaper seeking applicants for the position of Professor in Industrial Law in the Faculty of Law of the University of Sydney. I should explain here that the term ‘industrial law’ was the accepted name for labour law, certainly from the early 1900s to the mid-1990s.

This advertised professorship was an unusual position for two reasons. Importantly, and perhaps a little surprisingly, this was the first time in Australia that there was to be a designated professorship in the field of labour law. In part, this may have been because until relatively recently, labour law was not perceived as being part of the corpus of real law like commercial law, property law or criminal law. Although labour law had played a significant role in Australian politics and society throughout the twentieth century, it was not until the creation of this Chair that this sub-discipline of law received full recognition in academic circles. The second reason this professorship was a little unusual was because it was a five-year position rather than a permanent, tenured position. I thought to myself: well, so what? If the Chair is not renewed after five years, I simply go back to an associate-professorship. What have I really got to lose?

Mary and I had much to discuss. Our boys were two and four, and Mary had just completed the first trimester of her pregnancy with Kate. We had recently finished renovating a house and Mary was still working hard on her PhD thesis. If we decided to move to Sydney with a baby daughter and two small boys, we would be over 1000 kilometres away from Mary’s parents and from the rest of our families. I would find myself separated from my surrogate mum, Lois. We would need to find a suitable and accessible house, and to make new friends and look after our children without day-to-day grandparent support.

Mary realised that I was a little discontented at the Monash Law School. To progress my career I would have to move to another university. Aside from being a huge step in my career, we reflected on whether this move could open up further career paths for Mary. Mary took all of these matters in her stride, and jointly we decided to have a go.

We soon learned that I had been short-listed for this professorship. This meant that I would be required to travel to the University of Sydney to deliver a seminar to the Law School staff there and to appear before the interviewing panel.

Francis Trindade reminded me that most of the academics listening to my seminar would not be labour law experts. When I mentioned the highly technical topic I originally thought would impress them, Francis suggested I pick a more general topic that all the staff could understand and comment on. Ever since, I have given this advice to others. Pick a broad topic so you can engage with your entire audience.

Mary and I had never met the Dean of the University of Sydney Law School, Professor James Crawford. James happened to be visiting Melbourne in December 1991 and our dear friend, Father Frank Brennan, who knew James, arranged for us to have dinner with him.

That evening, Mary’s mum, Jacq, came over to look after the boys. Mary, who was eight months’ pregnant, dressed up for this special dinner. During the evening I could sense that James saw Mary and me as an interesting couple. This reinforced in my mind how being married to Mary had enabled me to be recognised as a senior academic and now a contender for a full professorship.

On Sunday, 12 January 1992 at 4.14 p.m., Kathryn Mary McCallum came into this world. It was the easiest of the three births. Frank Brennan was in town, and he and our family members all came in to meet our daughter. Kate seemed a much calmer baby than her brot

hers. If I was calmer with number three, I was no less delighted.

In the months that followed, I would often come home in the evening while Mary was feeding Kate in her highchair. The boys would rush to meet me, clamouring for my attention. Kate, not to be outdone, would make it very clear that she was a very special member of the family. Of course I would immediately scoop her up into my arms, baby bib and all. Even after Kate’s birth and a house full of small children, I could hardly believe that I was married to Mary and that we had this gorgeous family.

Back in Sydney, there was a delay with the interviews, so I didn’t fly up until Sunday evening, 9 February 1992. As Kate was less than one month old, Mary stayed at home nursing her and Lois accompanied me on this trip. On the Monday I delivered my staff seminar. I was of course a little nervous for the first thirty seconds but, once I got going, it was just like delivering a law school lecture and I fell into stride. As the topic was rather broad, I received a number of interesting and thought-provoking questions.

The following morning I met with the interviewing panel. I really wanted this position, even though it would be disruptive for Mary. It seemed to be the right career move for me. Answering all of the labour law and academic administrative questions was relatively easy. I was less sure about saying something about my special needs. If I raised this matter, would it be a factor in me not getting this job?

With some diffidence, I informed the panel that, if appointed, it would be necessary for the Faculty to purchase for me appropriate assistive technology. The Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Professor Sue Dorsch, simply said, ‘Yes, of course.’

Several years later, at a University of Sydney social occasion, I asked Professor Dorsch why she had shown such little concern over my need for special equipment. Sue said, ‘Oh, I guess you don’t know my story.’

Sue and her husband were doctors and they had several small children. One day her husband fell off a horse and was rendered paraplegic. Sue continued with her medical research and was the first woman to be appointed to a full professorship in the Faculty of Medicine. Later Sue became the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney. Her husband became an anaesthetist.

Little wonder that my technological requirements appeared so small in her eyes. I have always found that people who have either experienced disability directly or among their family or friends are the ones who show the greatest awareness of the issues confronting us persons with disabilities.

During that trip to Sydney in February 1992, I met Tim Noonan, an assistive-technology expert and Sydney native. Tim introduced me to the Braille ’n Speak device, which is best thought of as a tiny computer that can talk. It was like having pen and paper with me at each moment of every day, an unbelievable luxury. I used to carry it everywhere on a strap over my shoulder.

The Braille ’n Speak is the size of a large pocket book. Its keyboard is rather small, with braille cells being no more than six dots. Braille keyboards usually contain six keys for the six braille dots, and also a space bar, together with backspace and return keys. Some braille keyboards also contain two other braille cell keys for more sophisticated eight-dot computer braille. The Braille ’n Speak enabled me to write messages, notes and even articles in six-dot computer braille, which is a variant on the standard braille system. Then with the push of a button, the Braille ’n Speak would read me back in synthetic speech any files that had been either keyed in or copied to the Braille ’n Speak. Previously, I had always relied on memory for things such as phone numbers and addresses, whereas now I could store them easily. Besides brief jottings, I could also copy novels to the Braille ’n Speak, plug in a set of earphones and ‘read’ to my heart’s content.

Before such information-technology advances, I couldn’t easily write things down, and so I had to hold a great deal of information in my mind. From toddlerhood onwards, it was essential to learn techniques for remembering and thus to expand my capacity to remember with accuracy. Then, as a university teacher I had to remember so much legal material for each class that it all kept going around in my head.

In time I had two Braille ’n Speak computers. Mary said that when I only had one of them and it was out of service I was somewhat impossible to live with. So, it became important for family tranquillity for me to have a back-up machine.

After the interview at the University of Sydney we flew back to Melbourne, and that same evening James Crawford phoned and offered me the professorship. Mary was beside me. She signalled her joy, and so I accepted. I then had a long and somewhat sleepless night, tossing and turning while Mary got up periodically as she was nursing Kate every four or five hours.

The next morning, Mary’s dad, Gerard, called in just after breakfast. As he was a brilliant ophthalmologist, he had been appointed to his Chair at a much younger age than me. However, in his quiet way he gave Mary and me the courage to succeed with this new venture. As it turned out, I didn’t take up this position until 1 January 1993. We needed time for Kate to settle, also to find an accessible house in Sydney and for Mary to submit her doctoral thesis for examination.

In April 1992, Frank Brennan baptised Kate. This time the baptismal celebration at our home assumed a new poignancy as our thoughts were turning to our big move.

At the end of May 1992 we looked at a number of houses in Sydney, assisted by a relocation agent who was aware of our special needs as a family. We wanted to find a place on the Lower North Shore, because it was family-oriented and not as hectic as other parts of Sydney. We put a bid in for one, but disappointingly it was unsuccessful.

On 1 June 1992, the door of a house that seemed just right for us was opened by a Miss Isabel Hammond, then in her early eighties. The house was on a very large and somewhat overgrown block of land: the land size reflected an early attempt to make this area of Sydney’s North Shore attractive for families before the Sydney Harbour Bridge was opened in 1933. It was only 200 metres from the railway station. Built in 1922, the house needed some renovating, but we knew it could make a wonderful family home for us.

Later, Isabel told us that when she saw Mary and me her heart thumped and she knew she wanted to sell to us. We felt likewise. Mary flew up again, and she closed the deal. When we were well established in Sydney, Isabel became our surrogate grandmother. She often came to lunch on a Sunday and always stayed until the mid-afternoon. She remained a part of our lives for a good ten years, until she had a fall, was finally consigned to a nursing home and then died at the age of ninety-three.

House prices in Sydney at that time were considerably higher than in Melbourne. What helped us was that the University of Sydney agreed to pay the interest on part of our mortgage for five years. Looking back, this was an extraordinarily beneficial arrangement for us because it enabled us to live in a beautiful Sydney suburb that would otherwise have been beyond our reach.

With Kate’s arrival, we felt that our family was complete. We wanted to bring up our three small ones as well as we could, and of course Mary and I had careers to develop. Mary was well into her PhD thesis, and she was already preparing herself for future academic employment. Given my advancing age, it made sense for me to take the initiative in ensuring there would be no future pregnancies. So, when Kate was five months old I had a vasectomy.

Lois, my surrogate mum, drove me to the hospital for this small procedure. ‘Darling, you are indeed a fortunate man,’ she said. ‘You have a loving and gifted wife who has borne you two sons and one daughter. Whatever your future holds, you are now forty-three years old and you don’t need to be fathering any more children.’ Of course I agreed with the wisdom of dear Lois. It was a very small procedure, and nothing at all when compared with Mary’s three births.

Mary, her mum and baby Kate travelled to Sydney in October and November to oversee the renovations we regarded as necessary for the home we had acquired. It was a rather big job. The two women stripped the house of its old carpets, scraped back the ancient paint, and filled the cracks that had spread across the

walls and ceilings. The garden was a veritable jungle. It spilled into an ancient outhouse that served as a laundry, with original cement sinks and a dilapidated toilet that Mary worried was a perfect breeding ground for redback and funnel-web spiders. There was a massive fig tree just beyond the back door that we later found had spread its roots through all of the sewer system, from the backyard all the way down to the road.

I stayed at home in Melbourne. On the days that our nanny was not working, I took Gerard to his pre-school class at Brighton Grammar, took Daniel to the Monash Family Cooperative Crèche and tried to do a little work. I used taxis and had two portable child car-seats stacked by the front door. I called these trips ‘the milk runs’. Mary had arranged for a woman to come in and help me during the mornings and evenings, but even so it was rather exhausting.

Mary and I flew to Sydney on Thursday, 19 November 1992 to attend a cocktail party that Blake Dawson Waldron, the law firm that sponsored the professorship I now held, put on in my honour. I remember Lois helping me to purchase a new suit for this occasion. Mary had a jacket and skirt made by the same tailor who designed her wedding dress. We met a lot of important people, and it was the beginning of learning our way around the Sydney legal social scene.

On 8 December 1992, we all flew up to Sydney and moved into our new home.

I appreciate that my lack of vision is a real handicap in some situations. For example, I’m not very good at describing houses, even those in which I have lived for many years, perhaps because I do not have a picture of them in my mind. There was a master bedroom at the front of the house and it became Mary’s office when we became settled and she resumed her legal immigration practice. Mary and I moved into the second bedroom, while Gerard and Daniel slept in the third room in bunk-beds, and baby Kate had her cot in the final bedroom. There was a living room in the front and a kitchen at the back.

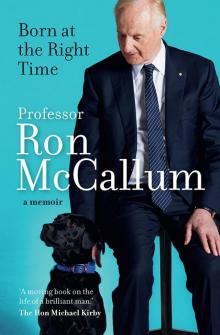

Born at the Right Time

Born at the Right Time