- Home

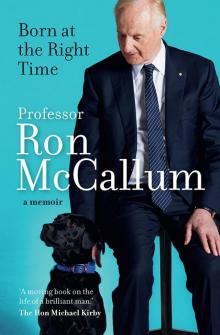

- Ron McCallum

Born at the Right Time Page 3

Born at the Right Time Read online

Page 3

When St Paul’s was established, Hugh was appointed head of music. He taught me the piano and how to read braille music. Although he could not see anything at that time, he also taught partially sighted students to read printed music. He told me he could see the music lines and staves in his head.

I well remember when I was about ten years old, Hugh played us Beethoven’s magnificent Fifth Symphony. He also loved the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, inculcating in me a passion for classical music that I have carried with me ever since. Hugh taught me musical appreciation to year eleven, and it was a subject I enjoyed and which presented no difficulties for me.

By the 1960s, mechanical braille printing presses had been invented but, to the best of my knowledge, no such press was yet operating in Australia. The printed books St Paul’s purchased came mainly from the Royal National Institute for the Blind in England. We received some American books, but they were mainly on religious topics. Thus, my early education was very British indeed. I remember in years three and four that the two most interesting books I read were With Scott to the Pole, about Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the South Pole, and The Nine Days Wonder, which chronicled the nine days in May/June 1940 when small craft took the retreating British army off the Dunkirk beaches and back to safety in Britain. Somewhat differently from sighted children of my time and age, I read far more English than Australian books.

I devoured all of the historical books in the tiny St Paul’s library, and I found the lack of books to be a real problem, which continued throughout my life. Of course, the information technology advances over the past thirty years have given me an abundance of literature that I never could have previously imagined.

In his own way, Brother O’Neill seems to have had an idea that I could become a lawyer. After some three or four years at the school, in an endeavour to encourage me, I remember him speaking to me of Dudley Tregent, the first blind lawyer of whom I became aware.

Dudley was blinded in October 1918 while serving in the artillery on the Western Front. He lost his sight shortly before the armistice, having just celebrated his twenty-first birthday. Having matriculated before he joined up in 1915, upon his return to Australia Dudley decided to enrol in Arts and Law at the University of Melbourne. With help from the newly formed Australian Repatriation Department, he succeeded and was admitted to legal practice in 1925. He established Dudley Tregent and Co, which proved to be a very successful Collins Street law firm. I recall meeting Dudley at a function many years later, probably when I was studying law myself. My recollection is that he was very polite, and had the high treble voice and the very soft hands of an old man.

At St Paul’s School, life was very busy. Every morning, we got up, washed and dressed, and then we all had to make our beds. As we wore uniforms, I didn’t have to worry about colour coordinating my clothing. I simply had to change my shirt, underwear and socks and find my pants from where I had thrown them the night before. I found tying my tie to be relatively easy. As a parent, I had no difficulty in teaching our two sons to arrange this aspect of their school uniforms. One skill I have never mastered, though, is that of the manicurist. As a child, Mum used to cut my nails. Without my Mary, this is still a task that can lead to nasty injuries if I am left to my own devices.

Being at a residential school, I suspect, is a bit like growing up as a child on an Israeli kibbutz. We were like siblings—in our underwear together. There could be no real secrets. That special relationship endures even today. Former President of the World Blind Union, Ms Maryanne Diamond, was also a St Paul’s alumna. There was no bullying and I had space to grow.

With the help of my friend Peter Walsh, I began listening to short-wave radio broadcasts in about 1961. Short radio waves enable broadcasting from one country to another and, before the advent of the internet, this was an important way of disseminating news. I listened to short-wave broadcasts fairly constantly, right up to when I was a young lecturer in law at Monash University. The BBC, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Voice of Germany and Radio Netherlands gave super news coverage. They also broadcast innovative programs on a variety of topical and thought-provoking subjects. As I couldn’t read newspapers, these broadcasts gave me a window into politics and social movements throughout the world. I also listened to Radio Moscow, Radio Beijing and, after the Russian takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1968, to Radio Prague.

I am sure that this short-wave listening greatly broadened my horizons. After all, the ABC of the early 1960s had very few current-affairs programs. If I hadn’t had short-wave access to the BBC, my outlook would have been far less informed. At St Paul’s I also became more familiar with a new development in tape recorders: the magnetised wire had been replaced by more durable magnetic tape.

As I got older, sport became a more important part of my life. As was the case with other residential blind schools, we used guide ropes for track-and-field work. These ropes were strung across the sports field in parallel lines, supported by poles. The blind runner would hold a sliding handle attached to the rope, being guided along the length of the rope. On sports days, I enjoyed the hop-skip-and-jump and became reasonably good at it.

At the age of thirteen, I joined one of four blind cricket teams in Victoria. We played on Saturdays at what was then the Victorian Association of the Blind’s ground at Kooyong. The competing teams were made up of men and boys, with some members being totally blind, and others partially sighted. It was here that I first met fine men who had spent all of their lives in sheltered workshops.

I believe that blind cricket was a game devised by blind men who were employed as basket makers. The men used their skills to construct cricket balls of cane or wicker. To ensure that the balls made a noise, they were filled with beer-bottle tops. They were weighted with a piece of lead, to give them substance and potential bias. The rules of blind cricket require the bowler to bowl under-arm. For the ball to make a noise, it must bounce at least once before and once after the halfway line of the cricket pitch.

I was a bowler, and before bowling a ball I had to call ‘Right!’ to the batter. The batter then would reply ‘Right!’, after which I would call ‘Play!’ and bowl the ball. To make it easier for batter, bowler and fielders, batters batted one at a time. This meant that the bowlers always bowled from one end, and the batters always batted from the other. Batters who were totally blind were allowed to have one of the partially sighted team members as a runner. So, when I batted and I hit the ball, my team mate would run for me. This is a sport I enjoyed into my early university years. It helps explain my continuing fascination with all aspects of domestic and international cricket.

In 1959 my oldest brother, Ted, left school aged fourteen. This was permitted under the law at that time. He started out taking a series of odd jobs, but later carved out a fine career in the transport industry with a multi-national firm, working his way up from driving trucks into middle management.

After finishing year six at our local Catholic school, my second brother, Max, moved to Hampton High School, where he stayed up until mid-way through year twelve. He left school to work for an insurance company, moving on later to employment in the Weather Bureau, where he developed expertise in the emerging field of computing.

My general living skills improved as I got older. Even as young as seven, I would help my brother Max prepare Mum’s coffee and take it in to her. In those days of relative privation, we used a liquid substance called coffee essence (derived from chicory), which came in a bottle. When a little of it was dropped into boiling water the concoction tasted a little like coffee. We had no electric toaster at that time, so we used to put bread under the griller of our gas stove. Max and I made fine toast. My mum ensured that my blindness did not in any way exempt me from household chores. From my early years, I took turns with my brothers to dry and later to wash the dishes.

In my last two years at St Paul’s we were given cooking lessons on Monday evenings after school. The staff were conc

erned about us using knives, so they were forbidden. However, I learned the rudiments of baking and I loved cracking eggs into bowls. This early training helped me later on. In many respects my early schooling gave me the basics of life skills that would carry me into adulthood.

3

A Normal High School, and the Magic of Tape Recorders

In September 1962 my father died of heart failure brought on by alcoholism and post-traumatic stress disorder. In some ways his death was a relief, for us as a family and no doubt for Dad’s tortured soul. In other respects of course it was very sad, especially as I had never established a father–son relationship with him.

On the day of his passing, the federal Repatriation Department ruled that Dad had been totally and permanently incapacitated by his war service. This meant that Mum received a war widow’s repatriation pension for the rest of her life.

Dad had always elected to pay rent for our Housing Commission home, even though he was given the option of buying the house with weekly payments. Upon his death, Mum went to work, obtained a war-service loan and eventually paid off the house. Mum started out as the companion carer of an elderly woman; she also began to do piece work at home. This is where workers receive payment for the number of items produced rather than the number of hours worked.

You know those women’s purses that have a metal clasp? Mum brought home a machine that attached metal clasps to purses; she never owned this machine, which remained the property of someone else. You had to insert the purse into the machine and put the metal clasp into position with a tool; you then pressed down hard to attach the clasp firmly.

That became one of the jobs in our home. It was quite complicated; my brothers would help Mum with her piece work but I couldn’t, so I was let off the hook. We did learn that, when either my mum or one of my brothers sat down in our living room to work with this machine, we were not to invite people in to socialise.

Dad’s passing and Mum’s receipt of the war widow’s pension meant that our family became eligible for assistance from Melbourne Legacy. Legacy was founded in 1923 by ex-servicemen from the First World War, who had promised to look after the families of their deceased mates. Our Legatee was Mr Tuckson. He happened to be a lawyer, and in my later secondary education he encouraged me actively to think about a career in the law.

Legacy also helped me and my family in another way at the time of my father’s death. In the 1960s, during the school holiday month of January, Legacy instituted a scheme to have Legacy country children stay with Melbourne families, and for us city kids to visit country areas.

In January 1963, I participated in this scheme and spent two glorious weeks with Colin and Patsy Till on their dairy farm. It was in Victoria’s western district in the small hamlet of Boorcan, which is halfway between Camperdown and Terang. During the next few years, each January I would return to the Tills’ farm. Colin and Patsy had no children of their own, so in some ways I became their child. I would trail around with Colin as he milked the cows in the big mechanised sheds. I would sit on the bales of hay after they were harvested, talking with him about nothing and everything. Patsy showed me great affection at home as we drank tea and I taught her how to play chess. This gave me first-hand experience of the anguish of childless couples who long for small ones of their own.

I had never before touched a cow or experienced how milking machines worked. So, there I would be with Colin in the dairy, learning how my milk travelled from the cow to my breakfast cereal. During my time there I met several other young boys and we would climb up to the top of a haystack. No one seemed to care about my blindness. It opened up a new world for me and gave me some experience of country life. Whenever I smell passing cattle or sniff newly mown grass, my mind goes back to that Boorcan farm and those long-ago January days.

During my last year at St Paul’s, when I was thirteen, Mum began to teach me to travel on my own. She realised that I would need to go to a ‘real’ school to complete my secondary education, and therefore it was important for me to travel independently.

First, I learned to walk by myself, with the aid of the white cane I had used from an early age, to the bus stop near our Hampton home. The bus went to Hampton railway station, and I learned to move from the bus stop to the station platform. On the train to downtown Melbourne I learned to count the train station stops. At Melbourne’s Flinders Street Station, I learned to walk up the ramp, to find the exit on to Flinders Street. I would then wait, holding my cane, until somebody offered to help me across to the island tram stop. On the tram, I would ask the conductor to let me off at Kew Junction. It was then a short walk up the hill to St Paul’s School. I remember the first day I travelled all that way by myself. Upon arrival I was absolutely exhausted, but happy.

Looking back at my time from kindergarten through to year eight at blind residential schools, I realised I learned very important life skills. Evelyn Maguire, Bill Holligan and Essie Eather had given me a superb primary and early secondary education. My braille reading and writing were excellent, and I have relied on these skills ever since. I had a good awareness of the world around me and had acquired a deep love of literature and of fine music. The dedication and love of my teachers gave me a confidence that probably underpins who I am today. In my case, the two residential schools spared me at least some of the family violence of my home life. This violence had in fact diminished as my brothers grew and our dad’s capacities diminished.

There were, however, negative aspects to the type of segregated education I experienced. It meant that I was removed from my local area and from the neighbourhood children. I suspect that my social skills were not as finely honed as they may have been had I received an integrated and locally based education. At the blind schools I was spared bullying but I did feel isolated. In some ways this sense of separation has endured, at least in my subconscious.

During my childhood there were no schemes in Australia for the inclusive education of blind children and of children with other disabilities. If such programs had existed, I wonder sometimes whether I would have received the same skills training. Would I have felt more a part of the community?

If a blind child is given sufficient support, there can be no doubt that integrated education in the local school system will enable them to participate fully in the community. However, it is crucial that the support is both adequate and well thought through. Integration also assists children generally, insofar as it exposes school-age children to persons with disabilities: showing them that we all inhabit the same world.

Following the death of my father, Brother O’Neill arranged for me to attend St Bede’s, a Catholic boys’ college in Mentone, a Melbourne suburb not far from my home, for the final years of my secondary education.

At this time, the Catholic schools were totally separate from the state education system. Initially, they received no government funding to assist with educating the Catholic girls and boys in their care. Of course things are very different today; however, I never received any form of state education. I am not sure whether I would have been admitted to a Victorian state high school at that time.

No doubt owing in part to Brother O’Neill’s influence, St Bede’s agreed to admit me for a trial month in 1963. At the end of my first month, nothing was ever said and so I remained until I completed year twelve in 1966.

I vividly remember my first day of school in year nine. Like most February days it was quite hot. I had been to Mentone railway station before, and accordingly, I told Mum that I wanted to travel to my new school on my own. Mum, bless her, agreed.

I caught the bus to Moorabbin railway station and then the train to Mentone. I was a little late and so I missed the main throng of students going to school. When I walked through the ticket office with my white cane, I made my way out to find a bus. There I was in my brand-new school uniform, my school cap and all, when a man named Jim Murphy approached me. He explained that he was a teacher at St Bede’s, that he was also a few minutes late an

d he offered to take me in a taxi with him down to school.

I learned later that Jim was the most gifted teacher at the school. He would teach me modern history and English literature in year twelve. I would even go so far as to say that his dedicated teaching was the primary reason that I got into law school. Interestingly for me, I learned later that Jim’s father had also been blind. This may explain why he had no difficulty in walking up to me as he did. He made me feel very secure.

I was placed in a group of between forty-five and fifty teenage boys in Class 3C. I will always remember the particular smell of the classroom: of chalk on blackboards, of over-ripe bananas in boys’ lunch boxes, of the ubiquitous sweaty socks and the sheer life-force aroma of pent-up young-male hormones.

There I was, seated at a desk, surrounded by the buzz and murmur of my new classmates, full of eagerness and anticipation. All seemed to be going well until the teacher hauled several of them out of their seats and lined them up in front of the class. Perhaps they had been horsing around—I had no idea what they had done from where I sat. The teacher moved along the line of them standing there, and he hit each of them on the hands with a leather strap. I had never before experienced anything like this in a classroom, and I stood up in my place and wondered whether I should leave the room. The teacher came over to me and told me not to worry. He said that he would never strap a blind boy. I tried to explain that this was my first day at a real school and that I had no idea that strapping would be used in the classroom. He told me again not to worry, and that a few strappings early on showed the class who was in charge.

Born at the Right Time

Born at the Right Time